Intellectual Property

The services offered by Packaging Forensics Associates, Inc. and covered in this website are for the protection of the rights of owners or creators of inventions that may be in an art form or as a packaged product that has functions or utility.

The US law covering Intellectual Property Law includes patents, copyrights, trademarks, and trade secrets. All of these areas are related in that they deal with protecting products created by a human mind, but the mind, in other ways, is unique and may have different functions they are very different.

Copyrights protect works such as art, books, published materials, and movies, among others, for the original creators of such efforts.

Packaging is a unique field that covers science as well as art. The four roles of packaging are containment, protection, utility, and communication. Developing packaging that provides the appropriate containment, protection, and utility generally requires scientific research and testing, whereas packaging with the most effective communication often requires a more subjective approach. At the most basic level of communication, a package should identify its contents. Consumers today are increasingly making purchasing decisions based on how products make them feel, so an effective approach to packaging communication not only describes the contained product but also elicits an emotional connection by appealing to the target audience's senses. Because a consumer typically interacts with the package first, it is imperative that the package engages the consumer.

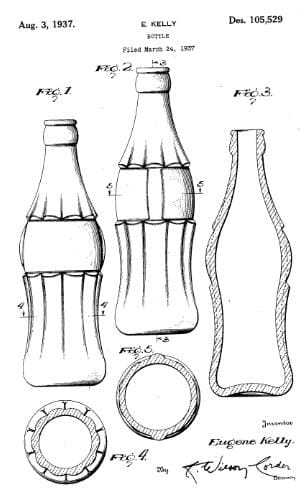

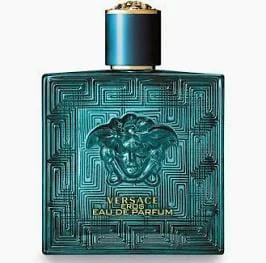

Utility patents protect the function/process or task done (how something works or is manufactured, or a process, etc.), whereas the design patent protects the 'ornamental appearance.' In most cases, utility patents are considered more valuable; however, design patents can provide long-term brand identification.

As products become commoditized, a package's unique design helps to create a distinctive product or brand that the consumer can easily identify. Proctor & Gamble, one of the world's largest consumer packaged goods (CPG) companies, has coined the phrase "First Moment of Truth" 4 (FMOT) to define a consumer's initial 3-5 second interaction with the product in a retail environment. The FMOT occurs in only a few seconds, so the necessity for differentiating one product from another requires a noticeable distinction between the two products. The need for unique and recognizable packaging necessitates a design-led approach. There is a seemingly limitless range of potential ornamental designs, including shapes, colors, and textures, and it's important for packaging developers to protect their unique designs and not have their designs copied or stolen. A design patent can be used to prevent such infringement.

There are mainly two main types of patents for the packaging field: utility patents and design patents.

A utility patent protects against infringement of the functional component of an invention, whereas a design patent protects against infringement of the ornamental features of a manufactured product. The granting of a patent does not guarantee protection against infringement, as the party accused of infringement has legal methods for defending their product. For infringement in a utility patent, the accused party will also generally try to invalidate the infringed patent by establishing prior art or other means. So when a case of infringement is brought by the plaintiff, the defendant will try to prove the invalidity of the patent holder's claims using prior art or scientific methods to prove to the court.

Historically, there have been two tests for determining infringement in the case of a design patent. However, since 2008, based on a court ruling, one test has been established for design patents, and it is called the "ordinary observer" test. This is a completely sufficient test for establishing infringement. The court will need to determine if the two products are substantially the same. If an ordinary observer cannot differentiate between two designs, then they are legally defined as similar. The accused party will need to prove their manufactured product is "plainly dissimilar" to an ordinary observer. The ordinary observer test was first established as a result of the 1871 Gorham v. White U.S. Supreme Court decision. Both the plaintiff and the defendant, in this case, put forth dozens of experts in the field of flatware, and the courts decided that an expert's opinions about what an ordinary observer would view are not as relevant as the ordinary observer's opinion. The majority opinion set the standard for the "ordinary observer" test, stated as:

"We hold therefore, that if, in the eye of an ordinary observer, giving such attention as a purchaser usually gives, two designs are substantially the same, if the resemblance is such as to deceive such an observer, inducing him to purchase one supposing it to be the other, the first one patented is infringed by the other."

Prior to 2008, in addition to the ordinary observer test, the "point-of-novelty" test was also used, and it stated:

"For a design patent to be infringed, however, no matter how similar two items look, 'the accused device must appropriate the novelty in the patented device which distinguishes it from the prior art.'"

In terms of the packaging field, bottles, caps, containers, composite compositions, laminations, materials, shapes, designs, filling and dispensing, manufacturing equipment and machinery, inspection, automation, labels, coatings, etc., are all patentable. In addition, the name of a brand can get copyright protection.

Examples of utility patents are Heinz Squeeze Ketchup Bottle and a separate patent for a cap with spill-proof dispensing.

Examples of bottle design patents are Coca-Cola bottles and Versace perfume bottles, among many others.